Separating Myth from Reality in Israel-Palestine

My family, like so many other Jewish families, has been at war since October 7. None of us are in uniform, but we’re barely speaking — and once I publish this, I’m afraid that the rift with some of them could be lasting. If I don’t publish, I know that living with myself will be impossible.

On the day that Hamas attacked Israel, we were united in horror, texting each other with news updates, or more observations, or just to connect. I couldn’t stop reading the back stories of the hostages, so many of whom were peace activists. When I closed my eyes, I struggled to not see young people running from a barrage of bullets.

But then came Israel’s response, launched like the apocalypse. “I have ordered a complete siege on the Gaza Strip,” said Defense Minister Yoav Gallant on October 9. “There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly.” He informed his troops that all restraints on their conduct had been lifted. To hammer the point, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu made annihilation a religious obligation. “You must remember what Amalek has done to you,” he said in a public address at the start of the ground invasion. I felt a chill up my spine.

That reference had deep significance for the religious nationalists in the military, who make up a growing portion of its officers. According to the Hebrew Bible, Amalek was a nomadic tribe of bullies and sinners that attacked the Israelites as they returned from slavery in Egypt. The Lord commanded Saul to wipe them out in the Book of Samuel: “Spare no one, but kill alike men and women, infants and sucklings, oxen and sheep, camels and asses.” When Saul disobeyed and let just one Amalekite survive, a descendant later tried to exterminate the Jews in Persia. Soldiers fully absorbed the implications of Netanyahu’s words.

Seven months and thirty-six thousand Palestinian deaths later, the Israel Defense Forces has made little headway in its alleged goal to destroy Hamas and return the hostages. It has, however, made lots of progress towards the religious directive — to erase all traces of “Amalek’s” existence. If you haven’t been following closely on social media or the few news outlets that use reports from Palestinian journalists, the dead might be a blur of numbers. But for some, like Dr. Tariq Haddad, a Virginia cardiologist, those numbers include more than a hundred family members. “Every single day I have to check and see who’s alive and who’s dead and who’s suffering,” he said on Amanpour and Company. One cousin died on her wedding day; another was about to receive her Ph.D. Among the rest was a physician, a pharmacist, a teacher, and children with dreams — none of them, Haddad added in weary exasperation, with any connection to Hamas. “They didn’t deserve any of this.”

There have been many savage wars during my lifetime: I won’t forget the killing fields of Cambodia or the genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia. But I’ve never seen anything like Gaza. Over two million people are now starving. All thirty-six hospitals have been destroyed or are barely usable. All twelve universities as well. Fifth-century mosques and churches, historical archives, museum artefacts from the Bronze Age, gone. The targeted hits on universities and schools are especially shattering and cruel, because Palestinian families prioritize education: it has been their only hope. Contrary to Israeli rhetoric about barbarism, Palestinians are known as the scholars of the Arab world, alongside the Lebanese.

Al-Israa University was less than ten years old. The campus included law and medical schools, the only university hospital in Gaza, and a new museum filled with antiquities, all built by the hands of the faculty. More than two-thirds of its students were women. “Mothers, single mothers; we offered so many scholarships,” said Ahmed Alhussaina, the school’s vice president, in an interview with Chris Hedges. “We had a motto that poverty will not stand as an obstacle for any Palestinian who wants to pursue a college degree.” Israeli forces turned Al-Israa into a military base. When they left, they seeded the building with mines and blew it up. “We were about to do a grand opening of the museum,” said Alhussaina. “It was looted out; end of story. Everything went away in the blink of an eye.”

Making Gaza unlivable clearly has been the plan all along. Dana Mills is an Israeli writer and peace activist who was hit hard by the Hamas attack in Israel. She knew several people who were murdered or kidnapped; members of her family were displaced. Despite her own trauma, her fears on October 7 went to Netanyahu and what was coming. “It felt like this was the perfect storm for him to just go and do something that we knew he had wanted to do, which was to create a huge amount of misery and devastation and suffering, and ensure that there will never be an independent Palestine of any kind. Not two states, not one state, not no state,” she told Owen Jones, a reporter for The Guardian, on his YouTube channel.

Most of my family and Jewish friends have had nothing to say about Gaza and are offended by those who do. We now live on different planets. While I can’t bear to see another child coated in grey dust after having been dug out of rubble, my family’s outrage is directed at college protesters and anyone who uses the word “occupation” or “apartheid” in reference to Israel. All they can see is anti-Semitism, and they see it everywhere. They post about how unsafe they feel in their peaceful, progressive neighborhoods.

One young cousin’s Instagram story in December, as all of Khan Yunis was being flattened, left me speechless and heartbroken: “We interrupt this war against the Jews to celebrate Hanukkah, another war against the Jews. (Spoiler alert: we won that one too.)” How did my compassionate family, always on the side of the marginalized and oppressed, become unrecognizably myopic? How can they cheer on this slaughter?

I know at least part of the answer. In the eyes of my cousins, the Hamas attack was a random act of evil that grew out of anti-Jewish indoctrination. For me, it was awful but predictable, and had nothing to do with religion. The disconnect between us: my family knows only the sanitized version of Israel’s history, the one in which Jews were and are perpetually victims.

We all were told that Palestine was barren and uninhabited before the Zionist movement in the early 1900s. In truth, half a million Arabs were living there when European Jews first showed up to declare it Eretz Yisrael, the land of the Jewish people, biblically ordained. Arabs were the majority population for at least thirteen centuries and enjoyed a good relationship with the small Jewish community in Palestine. But as the European immigrants bought up land, they began evicting the Arabs who had been farming it. Tensions spilled over to periodic violence, which continued back and forth in the decades before the UN vote on partition.

“Of course the Palestinians resisted Zionism,” said Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, director of the European Centre for Palestine Studies at the University of Exeter in England. “As long as someone knocks on that window and says ‘I used to live there two thousand years ago,’ it’s okay. But if he begins to live in my house, I will try and kick [him] out. It’s a natural right of colonized people to try and kick out the colonialists… Now, Israelis don’t understand it. Israelis don’t know that they colonized Palestine. They really think they came to an empty land and these nasty Palestinians started to attack them.” Pappé has said that he believed the same while growing up in Haifa and serving in the army. It was not until his doctoral work at Oxford, when Israel began declassifying military files from the period, that he was first confronted with the truth.

My understanding as a child was that most of the Palestinians then left voluntarily in 1948, after the neighboring Arab countries invaded the new state of Israel. I never questioned why they didn’t return home after the war. My parents said they just refused to live alongside Jews.

I got a radically different story on one of my first dates with my future husband, a Lebanese-American, in 1987. This was the first I’d heard about Palestinians being violently chased from their homes, and I still remember the adrenaline and anger of cognitive dissonance. I argued, called him an anti-Semite, as we do, and nearly walked out on dinner. But once I researched what Palestinians call the Nakba, or “catastrophe” in Arabic — the forced expulsion of seven hundred and fifty thousand Arabs in 1947–48 — I had my own epiphany, and began to see the elaborate ecosystem that supports this central lie.

There are two components to the lie. One denies the Nakba; the other purposely muddies chronology. As the official story goes, Zionists had accepted the UN partition plan and were prepared to share the land with Arabs, but as soon as they declared the state of Israel, they were attacked from within and from multiple countries. It was in the course of defending itself, according to Jewish mythology, that Israel destroyed Arab villages.

Here are the flaws in this narrative. Israeli military archives show that Zionists had methodically razed Arab villages and expelled Arabs from cities well before the war. Their intention to form a Jewish majority state had been articulated from the beginning, and that obviously wasn’t possible when they made up less than a third of the population. “The only solution is a Land of Israel devoid of Arabs,” wrote Yosef Weitz, who managed Zionist land acquisition, in his diary in 1940. “There is no room here for compromise. They all must be moved. Not one village can remain, and not one tribe.”

Zionists had a chilling manual for getting this done. Known as Plan Dalet (Hebrew for “D”), it called for planting explosives, burning down homes, and leaving landmines in the debris to keep Arabs from returning. Jews even poisoned the wells in some Arab towns, under a secret project led by David Ben-Gurion, the “father” of Israel. It worked: resulting outbreaks of disease did cause Arabs to abandon their homes. Psychological warfare was another tool, as detailed in a 1948 intelligence report uncovered by the Israeli NGO Akevot. Soldiers blasted frightening sounds from loudspeakers mounted on trucks — screams, sirens, emergency warnings in Arabic, which panicked residents and triggered a stampede to evacuate.

As I re-read descriptions of the Nakba massacres, they sound uncomfortably like the Hamas attack. Two Zionist terror groups, the Irgun and Stern Gang, launched a surprise raid on the village of Deir Yassan a month before the creation of Israel, even though residents had signed a nonaggression pact. According to a report filed by British administrators in Palestine, militants stripped women and children, lined them up, photographed and executed them. Other residents were tied to a tree and set on fire. Young, female survivors told police they had been raped. Several men were taken hostage and paraded through the streets of Jerusalem, where onlookers spat on and kicked them before they were killed.

Six months later, in the village of Safsaf, the newly formed IDF — which had absorbed members of the terrorist groups into its ranks — tied dozens of men together, threw them in a pit, and shot them. Some of their bodies were still twitching when they were covered with dirt, in the words of an Israeli soldier who kept inventory. A fourteen-year-old girl was raped, he wrote, as were two other women. Soldiers cut off a man’s fingers to take his ring.

I offer these gruesome details simply to contrast them with the fairy tale that Jews continue to be fed. My previous education about this period came from watching Exodus as a pre-teen, crushing on the adorable Irgun fighter played by Sal Mineo. I don’t think I’d be wrong in guessing that most Jews still have no idea that the Irgun and the even more militant Stern Gang were responsible for assassinating dozens of political figures, blowing up buses and buildings, and killing and raping the residents of Deir Yassan. Their members proudly identified as terrorists: “Neither Jewish ethics nor Jewish tradition can disqualify terrorism as a means of combat,” a Stern Gang member wrote in their underground newspaper in August 1943.

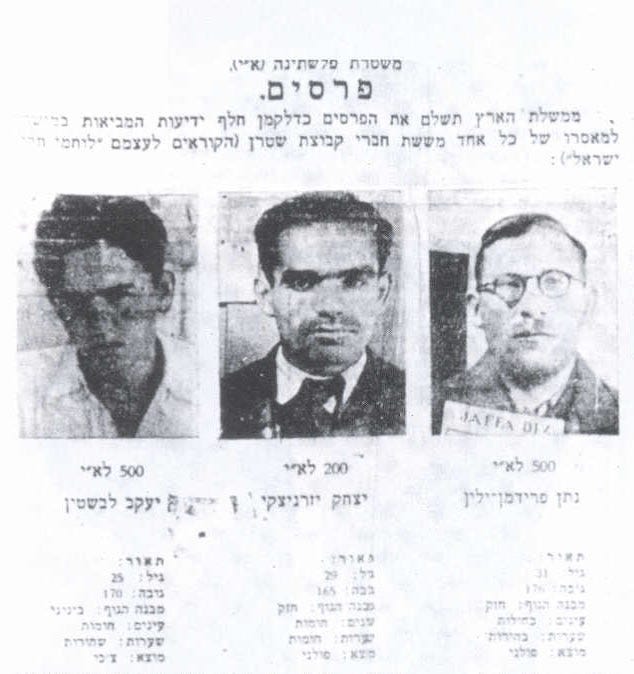

Israel has never called its own terrorists “animals,” as it does Hamas, or even terrorists. Instead, it has honored them with commemorative stamps — the “Martyrs of the Struggle for Independence” series — plaques, streets named for them, and stewardship of the country. Menachem Begin, who as Irgun leader masterminded the bombing of the King David Hotel in 1946, was elected prime minister thirty years later. A leader of the Stern Gang, Yitzhak Shamir, followed Begin in office, despite having overseen two spectacular assassinations.

Most Palestinian survivors of the Nakba still have keys to the homes that they fled in fear, hoping one day to return. But few have even been allowed to walk those streets again, no matter how close to where they live now. At age seventy, Mohamed Hadid, father of models Gigi and Bella and a prominent real estate developer in Los Angeles, managed to take a selfie in front of his family home in Safad, thanks to the perks of fame. Mohamed’s house had been seized in 1948, when he was an infant. According to his daughter Alana, her grandparents had let Jewish refugee families from Poland stay in their guesthouse after World War II ended. When Palestine was reinvented as Israel two years later, her grandfather returned home from work one day to find his non-valuable belongings on the front lawn. The Polish refugees had moved into the main house and soldiers were blocking the door. “My grandmother had just had a child and she already had young daughters,” Alana told Middle East Eye in February. “She put her kids literally on a donkey and they walked to Syria.”

It was this stream of refugees, tens of thousands of them pouring into Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, that Pappé and other historians say was the real reason for the war: Arab citizens pressured their reluctant governments to invade Israel and stop the ethnic cleansing. By its end in 1949, Israel controlled nearly 80 percent of the land that the UN had intended to be split with Palestinians. The rest — Gaza and what we now call the West Bank — went to Egypt and Transjordan, respectively. The Palestinians got nothing. They moved into tents in refugee camps and have remained without a country or civil rights for the past seventy-six years.

Owning up to the lies in your cultural narrative has a price: my estrangement from a beloved cousin has left my heart in pieces. Decades of censoring myself also took its toll, though. I was so afraid of angering my brother, a religious and ardent Zionist who was a second father to me, that I mostly avoided writing about Israel. It took a two-thousand-pound bomb on the Jabalia refugee camp last October for me to stop worrying about my family’s reaction. I can’t be complicit in what I see as a genocide.

To my surprise and relief, I wasn’t alone. Once I started research for this article, I found a large community of like-minded Jews who have faced far more upheaval than me. Some were raised in hardline families in Israel, some attended Jewish schools and summer camps in the diaspora, some served in the Israeli military. By speaking out, they braved social ostracization and death threats. Almost all trace their awakening to the first time they visited the West Bank and saw that “apartheid” wasn’t the anti-Semitic slur that they’d been told, but a sickening reality — where Palestinians live under the thumb of the military and at the mercy of extremist Israeli settlers, whose mission is to confiscate their land. My new favorite podcast, Disillusioned, is a series of interviews with Israelis who shed their indoctrination and have been working for Palestinian rights.

But rejecting the mythology is still the easy part. It is more painful to investigate the underlying behavior, which contradicts everything I’d been raised to believe were Jewish values. Long ago, when I first heard that Jews had appropriated Palestinian homes, I couldn’t believe they would do something so deeply immoral, not to mention what the Nazis had just done to them. Now that IDF soldiers can’t stop sharing their war crimes on TikTok, I have fewer illusions.

My family probably hasn’t followed the IDF videos, or anything that challenges their belief in “the world’s most moral army.” To much of the world, though, the Israeli army is the new face of evil on their phone screens. I have watched soldiers gleefully blow up homes and turn explosions into save-the-date celebrations with song and dance. I’ve seen them laugh while they vandalize small businesses, loot and defile intimate keepsakes, destroy household belongings out of spite. All are hard to watch. But the ones that make my skin crawl feature men rifling through Palestinian women’s negligees or trying on bras and thongs over their uniforms. There are many such videos; each feels like a violation.

I don’t want to talk about Hamas here or compare war crimes. It is obvious to me what created Hamas. Until recently, I was less aware of what created the deep hatred for Arabs among Israelis and many diaspora Jews — a hatred that predated the Hamas attack by many decades and has sustained the brutal occupation. But the mystery is lifting.

There is widespread belief in the Jewish community that Palestinian children are indoctrinated in school to hate Jews. My cousins believe this, although a German study of Palestinian textbooks, commissioned by the European Union, proved them wrong. It’s another example of every accusation being a confession: in researching her two books on Israeli textbooks, Hebrew University of Jerusalem professor Nurit Peled-Elhanan found that Palestinians appeared in the pages only as “racist caricatures of Ali Baba on a camel, primitive farmers following oxen, or terrorists.” Never a teacher, a lawyer, a child, a real human being — making it easy to demonize them. “Ever since we befriended Germany in 1953, the Arabs received the role of potential exterminators,” she said in an interview in February. “The idea is that since we are the eternal victims, we have to be very strong and domineering in the area, in order to prevent another Holocaust. And that’s the main foundation of Israeli education.”

According to Peled, Israelis are force-fed images of emaciated children and explicit Nazi barbarism from early childhood. “Can you imagine what happens to Israeli children when they are exposed to these photographs from the age of three?” she said. “They are afraid of anybody.” In high school, they travel to Poland to visit Auschwitz-Birkenau. “They go to the death camps wrapped in Israeli flags, accompanied by armed Israeli soldiers, and they come back nationalists imbued with the urge for revenge. But the revenge is not towards the Germans.” Their rage is against the Palestinians, who have blended with Nazis in their minds. “It’s a very sophisticated education that really educates the children to take revenge on the wrong people.” Her assessment comes with the moral authority of personal tragedy: Peled’s fourteen-year-old daughter was killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber in Jerusalem in 1997. Then and now, she holds her government responsible — for denying Palestinians any peaceful avenue to gain their freedom in the West Bank and Gaza.

For decades, some prominent voices within Israel have warned about the repercussions of terrorizing and radicalizing the population — especially under Netanyahu, who has been called the greatest fearmonger in the country’s history. An already traumatized population soaks up the message especially well. “The next generation removed from people who have experienced mass violence have a more exaggerated stress response to perceived threat,” said Katherine Bogen, a trauma therapist and granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor, in an interview. “And when you have an exaggerated stress response, you really do internalize ‘it’s us or them, kill or be killed.’”

Now that October 7 realized their worst fears, the fruits of this indoctrination are on full display. Foreign doctors volunteering in Gaza have seen a stream of children murdered or in a vegetative state from a single sniper bullet, indicating that they were targeted. “You can maybe argue that a bomb went off and a kid just happened to be nearby, but it’s not believable that the best-trained marksmen in the world accidentally shot a three-year-old boy in the head, accidentally shot a two-year-old girl twice in the head,” said Dr. Feroze Sidhwa, a trauma surgeon from California, in an interview with Democracy Now after returning from Gaza.

I try to imagine the level of brainwashing it takes for soldiers to shoot a three-year-old. Perhaps they heard from their rabbis that even children were legitimate targets? Rabbi Eliyahu Mali is the head of a yeshiva in Jaffa that combines religious education with military service. “The Torah does not allow you to let every soul live,” he told students in March. They wanted to know: What about the elderly? What about children? The same, the same, he replied. “Today he is a child, today he is a boy, tomorrow he is not.” Mali is not alone. A popular internet rabbi with half a million YouTube followers teaches that babies must be identified as “non-militant” before being safe from execution.

That they regard Palestinians as less than human beings is obvious. Soldiers randomly round up men and boys in Gaza — from doctors inside hospitals to journalists and their camera crew to grandfathers in shelters — and hold them in Israel sometimes for months without charges. Upon release from detention centers, Palestinians tell matching stories of torture. According to a doctor at one of the Israeli centers, who sent a letter of complaint to government officials, all detainees at his facility are kept blindfolded and cuffed at wrists and ankles, day and night. The resulting infections and blood clots have led to amputations of their limbs on a regular basis. Detainees are also forced to defecate in diapers and eat through straws, he wrote, which has caused them to lose large amounts of weight. “Guantanamo starts to seem as a resort place,” said Haaretz columnist Gideon Levy.

Humiliation is a key component of nearly all interactions between the IDF and Palestinians, inside or outside of detention. Alhussaina, the vice president of Al-Israa University and an American citizen, was shocked by his treatment when moving his family from Gaza City to southern Gaza in November, as ordered by Israel. Like everyone else on the road, they had to leave their car and stand in the sun for two-and-a-half hours, arms above their heads holding an ID card that they prayed wouldn’t fall and get them shot. “They call you [over]: ‘the donkey with the red shirt,’” he told Chris Hedges on the Real News Network. Everyone had to strip naked, men and women alike. “All this humiliation. A 70-year-old man had to stand there and take all his clothes off, and they make him turn around in front of the people. …Women were crying, kids were crying. My granddaughter is three years old; she was horrified.”

It has been this routine, entrenched sadism that leaves me sick to my stomach. What civilized society withholds food and water from children? Those in the north are eating grass and donkey feed to stay alive. To put things in perspective, international agencies are calling Gaza the worst hunger catastrophe in recorded history, in terms of scale and speed. This, while hundreds of truckloads of aid wait in Northern Sinai, blocked by Israel from entering. By all independent accounts, the IDF will arbitrarily turn away an entire truck because they object to one item. Examples of threatening items that have cancelled a food delivery, according to the International Rescue Committee: a pair of scissors, sleeping bags, crutches, anesthesia.

Even worse is the spectacle of Israeli citizens sabotaging food delivery in the middle of a famine, first by blocking the border crossings and later by hijacking aid trucks. In March, a video report by The Grayzone, documented how IDF soldiers aided the border blockades. Instead of doing their job and facilitating aid delivery, soldiers escorted protesters to the crossing gates — a restricted security zone — and then cynically used their presence in that zone as an excuse for closing the crossing, sometimes for days.

The situation has only gotten worse. When Israel started its invasion of Rafah in May, it closed the crossing where most aid was going through, slowing food delivery to a trickle — or nothing. At the same time, crowds of Israeli settlers and other extremists began commandeering aid trucks, beating up the drivers, and emptying bags of rice, sugar, and flour on the road. They set at least one truck on fire. Not only have soldiers and police stood by without intervening, but they actually have been tipping off the settlers, according to the Guardian.

“This cruelty is beyond words, and the silence of the rest of the Israeli society watching this unfold day after day is deafening,” Yahav Erez, creator of the Disillusioned podcast, wrote on Instagram after videos of the destruction started appearing. “Recently I learned of a term that is familiar to professionals who work with war veterans — ‘moral injury.’ This whole society has been heavily ‘morally injured’ and doesn’t even want to start looking for ways to heal from it. Everything about this scene is so ‘Clockwork Orange’ that I can hardly bear to look.”

Netanyahu tweet: “This is a struggle between the children of light and the children of darkness, between humanity and the law of the jungle.”

The gaslighting has been relentless, unbearable. I have spent countless hours watching news footage of the IDF committing war crimes, and later seen a spokesperson deny they ever happened, or offer some preposterous rationale. When soldiers bulldozed at least sixteen cemeteries and dug up the corpses, the IDF claimed to be looking for Israeli hostages inside the graves.

So far, the Netanyahu regime has gotten away with it by delivering lie after lie in rapid succession, Trumpian style. By the time we start investigating one dubious claim, they are on to the next. But their lies have had enduring consequences — particularly those that justified the destruction of Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City.

Under international law, attacking hospitals is a serious war crime, with only one exemption: if a hospital is being used militarily to inflict harm on the enemy. I doubt it’s coincidence that before storming Al-Shifa in November, Israeli officials claimed that Hamas was using a bunker and tunnel system under the complex for its military headquarters, and that the system connected to hospital wards. A video presentation for reporters showed 3D-simulated fighters moving through tunnels in camouflage gear, as imagined by Israel. There was also audio “proof,” courtesy of a comical, allegedly intercepted conversation that confirmed Israel’s hypothesis within thirty seconds. It boggles the mind that there was no pushback from foreign journalists.

“So, where are the main headquarters of Al-Qassam Brigades*?” a man’s voice challenged the woman on the other end of the line to guess.

“I don’t know,” she replied. Where?

“Under the compound Al-Shifa,” he said.

“God forbid! Are you serious?”

“Yes, the leadership headquarters are under the Al-Shifa compound.”

“Oh my!”

*the military wing of Hamas

After the siege, which killed many patients, a Washington Post investigation found no evidence to support Israel’s story about a command center. Neither did it show a way to access the hospital from the tunnels. Months later, the IDF said that the tunnels weren’t as important as they thought. Or claimed to have thought.

All of this matters. The dog and pony show for Al-Shifa gave Israel cover as it destroyed hospital after hospital — and even as it circled back to Al-Shifa in March, this time asserting that Hamas was inside the wards and operating rooms. Artillery fire rang through the corridors for two full weeks, killing many patients and at least two doctors. On their way out, soldiers set fire to the dialysis unit, the radiation unit, the maternity ward, everything they could torch. The hospital has been completely gutted.

No doctors or other witnesses reported seeing Hamas fighters. But they did see and smell the hellscape that the military left when it withdrew on April 1. The hospital courtyard was covered with hundreds of dismembered bodies and an overpowering stench. “I have been working nonstop for the past six months covering what’s happening in Gaza,” wrote Palestinian reporter Hossam Shabat on X, “but what I saw today while visiting Al-Shifa hospital was unlike anything I’ve ever witnessed before. …The bodies were in horrific conditions; many had their hands and legs tied behind their backs and were flattened by a bulldozer. Many of the bodies were burned and left to be crushed to pieces. Several bodies were decomposed and partly eaten by stray dogs… families could only identify them by their clothes.”

Israel called the mission a success, with no civilian casualties.

It took the deaths of seven aid workers for the World Central Kitchen in April for the media to finally challenge Israel’s versions of events. Thanks to the celebrity of Chef José Andrés, and the white skin of six of the victims, reporters bothered to track down enough details to conclude that they were deliberately killed, and that the IDF hadn’t really seen a Hamas fighter in the convoy, as it first claimed. According to an article in The Telegraph, which is usually staunchly pro-Israel, the commander in charge that night was an extremist settler who had petitioned the Israeli government to block humanitarian aid into northern Gaza.

There is a reason I am belaboring these lies, as tedious as they may be to read. I recognize how much evidence it takes to counteract cognitive dissonance. I also know it will be tempting to dismiss what I say next — unless there is a longstanding pattern of disinformation by the Israeli government.

When my very dear cousin closed down to discussion about Gaza, she had reached her limit of October 7 atrocities, which were playing on repeat in the media. “I don’t relate to anyone who supports, sympathizes, or apologizes in any way for people who can bake a baby alive,” she said in a text. “That’s just a line in the sand for me.” The same for someone who can “cut off a woman’s breast while raping her and play catch with it in the street before shooting her in the head.” She told me that although she once wanted to see firsthand how things were in the West Bank and Gaza, she no longer cared about context.

I shared her disgust. Who didn’t? But as it turned out, none of the unspeakably vile acts in the headlines those first days actually happened. To be clear: the slaughter and kidnapping of innocent civilians did happen and were inexcusable. I don’t condone violence in any form, for any reason, and Hamas committed horrible war crimes that were bad enough without wild invention. There were no beheaded babies, no babies baked in ovens, no women’s breasts cut off. Two babies died on October 7: one was hit by a blind shot through a safe-room door, the other died after an emergency Cesarian that was performed because the mother was shot. The corrections have been reported in Israeli newspapers, but not much in North America and Europe. “Forty decapitated babies” remains imprinted on people’s brains. Even Joe Biden kept repeating it long after his staff corrected him.

A single person was the source for many of these stories — a senior volunteer for Zaka, which is an ultra-Orthodox group that gathers human remains for religious burial after a disaster. The press couldn’t get enough of volunteer Yossi Landau and his elaborate tales of horror. He repeated many times how he found a pregnant woman face down in a pool of blood, her stomach butchered open, the fetus stabbed but still attached. With each repetition, Landau collapsed in tears. And none of it was true. “This horrific incident, which the Zaka volunteer alleged occurred in Be’eri, simply didn’t happen,” Israeli reporter Aaron Rabinowitz wrote in Haaretz. It was “one of several stories that have been circulated without any basis.” Another of Zaka’s grisly stories was recited by Antony Blinken, the US Secretary of State, in front of Congress. That one didn’t happen either.

There were two things that may have sparked Landau’s imagination. First, Zaka was desperate for donations. As a Haaretz investigation revealed, the organization went from near bankruptcy at the beginning of October to almost fourteen million dollars in donations by January, thanks to Landau’s emotional public appearances. But Zaka volunteers also were urged on by Netanyahu, who gave them a pep talk in November. “[W]e need to buy time, which we also buy by turning to world leaders and to public opinion,” he told them, according to the official transcript. “You have an important role in influencing public opinion, which also influences leaders.”

As influencers, they were very, very good. These sensational atrocities are what people still cite in defense of Israel, whether in conversation or on social media, and politicians mention babies in ovens all the time. They are what allowed Israel to call Hamas, and by extension Palestinians, human animals. They are what condoned a supremely disproportionate assault on Gaza.

That leaves the most inflammatory topic. Although no victims have come forward, I don’t doubt that there were individual cases of rape on October 7. But there were many red flags in Israel’s narrative about widespread and systematic rape. Even the timing of that accusation caught my attention. On December 5, when Israel was getting heat for inflicting massive casualties after a week-long ceasefire, Netanyahu suddenly began railing against women’s organizations that he said had shown no concern for Israeli rape victims. “Where were you?” he asked rhetorically at a press conference. “Were you silent because it was Jewish women?” It was the first I’d heard about mass rapes, and it made me suspicious when he threw in anti-Semitism. The whole thing smelled like a diversion.

Months later, The Grayzone revealed that a pollster working for two pro-Israel lobbies had run focus groups to determine which atrocities most inflamed the public. “Raped civilians” topped the list, polling far better than murdering or burning them. The lobbyists then held meetings with politicians to tutor them on the best language to use about Hamas in speeches — a list that included “unthinkable savagery,” “barbaric atrocities,” “massacred babies,” and “raped women.”

I can’t say whether an independent investigation will prove that there were systematic rapes on October 7, or whether Israel will ever allow the UN or another body to seriously investigate. So far, it hasn’t. I can say that the big New York Times investigation, often cited as proof positive that Hamas had weaponized rape, was deeply problematic and its evidence has completely unraveled. Family members of the central victim disputed that she had been raped. Later, new video evidence made it highly unlikely that the other victims identified in the story had been raped either. The Times cut ties with one of the reporters, an Israeli filmmaker, after a review of her social media showed that she had liked a murderous tweet about Palestinians.

Meanwhile, there has been no more mention of the “tens of thousands” of testimonies that Israeli investigators said they had taken from alleged rape survivors and witnesses.

As I write this, Congress and the media are obsessed with pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses, the supposed hotbeds of anti-Semitism making Jewish students feel unsafe. Even if the charges were valid, it strikes me as obscene to focus on how Jews feel about opposition to a genocide while ignoring the genocide itself. Hundreds of Palestinian bodies are right now being pulled from mass graves at Gaza hospitals, some showing signs of having been buried alive. That story has been pushed out of the headlines. I am ashamed that my community is taking all the oxygen. But even more, I am furious that anti-Semitism is being used as a cudgel to censor criticism of Israel.

Jewish students are in fact a major part of the pro-Palestinian movement. Some of them are descendants of Holocaust survivors; some are observant and have held Shabbat services and seders in the encampments (joined by Muslims and Christians). None of that is getting attention. The Jewish students invited to speak on news shows are invariably those who feel unsafe. As satirist John Oliver summed up the insanity, after police at Dartmouth College dragged a sixty-five year old professor along the ground and zip-tied her: “That woman is not only Jewish, she’s a professor of Jewish studies. Yet she’s being brutalized by police supposedly there to keep Jewish people safe.”

And what does “safe” mean exactly? With all the media hysteria, I doubt people realize that there hasn’t been actual violence directed at Jewish students, on or off campus. What they typically say in interviews is that the slogans and signs and flags feel threatening. I can understand. Having your world view challenged is disorienting and scary. I’ve been there and have compassion for them. But exposure to other stories is part of learning, part of the university experience, and not the same as being unsafe.

Those who have documented reason to be scared — and who no one is rushing to protect — are Palestinian students and their supporters. Since October 7, they have been shot and left paralyzed; intentionally run over; sprayed with a noxious chemical; and attacked with wooden planks, fireworks, and mace by a pro-Israel mob while the police did nothing for hours. The facts didn’t stop Netanyahu from demonizing them and ratcheting up fears within the Jewish community. “Anti-Semitic mobs have taken over leading universities,” he said in April. “They call for the annihilation of Israel. They attack Jewish students. They attack Jewish faculty. This is reminiscent of what happened in German universities in the 1930s. It’s unconscionable.”

What is unconscionable is Netanyahu’s weaponization of anti-Semitism and his gaslighting. The student protesters have been adamantly inclusive. Like so many other Jews, they are tired of being told by Republicans with ties to neo-Nazis that their anti-Zionism means they are anti-Semitic. That false equivalency is glaring: the majority of Zionists, by far, are Christian evangelicals for whom Jews are a means to an end and expendable. According to their beliefs, Israeli Jews are necessary to set in motion Armageddon and the Second Coming of Christ — at which point those who don’t accept Jesus will die. So Netanyahu has set up a nonsensical situation whereby a large sect of Orthodox Jews who don’t accept the state of Israel are de facto anti-Semites, yet the founder of Christians United for Israel, who famously wrote that Hitler was sent by God to return the Jews to Israel, is not.

This censorship also feels fundamentally anti-Jewish. One of the things that I treasured most about my upbringing was the encouragement to question and debate, to be politically engaged. My parents were committed to Israel, but I believe that they would have been appalled by what is unfolding now. Empathy and commitment to social justice were what I was taught, not blind support for any government — and certainly not paranoia, cruelty, and vengeance.

“Be boldly critical of Israel — not despite being Jewish, but because you are. There is no tradition more central to Judaism than prophetic truth-telling…,” wrote Bernie Steinberg in The Harvard Crimson in December. Steinberg had served as executive director of Hillel at Harvard for eighteen years and was so disturbed by congressional grandstanding over anti-Semitism that he pulled together the op-ed while dying from cancer. In May, the House passed a bill that would make certain critiques of Israel a crime — such as calling it a racist state or drawing comparisons with Nazi policies. Steinberg didn’t live to see the legislation, but the words he left behind were rebuke enough: “If Israel’s cause is just, let it speak eloquently in its own defense… Smearing one’s opponents is rarely a tactic employed by those confident that justice is on their side.”

Sadly, the campaign is working. The prospect of receiving death threats, or getting fired or blacklisted, has left people afraid to criticize Israel, which has allowed disinformation to flourish. I feel like we’re back in the Trump years, when every accusation was projection and every day brought new gaslighting. What baffles me is that my family and friends were expert at seeing through all of it. Where did that awareness go?

Once again we are told that day is night and up is down. Here’s a well-worn example: “Hamas uses human shields and hides among civilians.” Israel has been making this claim for at least two decades, as justification for the massive civilian casualties the IDF has inflicted. It is repeated as fact by politicians, journalists, government officials, and my family without actual proof. According to investigations by Amnesty International of two major wars in Gaza, in 2009 and 2014, there was no evidence that Hamas had used civilians to protect them. Instead, Amnesty documented several instances of Israeli soldiers forcing Palestinians to act as their human shields. The Israeli human rights group B’Tselem describes it as a longstanding practice by Israel, and IDF soldiers themselves have testified to using it routinely. Recent video evidence shows that the practice continues, despite court orders to stop what is a war crime.

It would not bode well for Israel if Jews started seeing these contradictions and asking questions, as college students are doing. Widespread awareness would inevitably lead to support for BDS — boycott, divestment, and sanctions — the movement that brought down apartheid in South Africa and is at the heart of student protests. That is surely why Netanyahu has blurred the line between Israel and Jews: to lead all of us into an emotional state of high alert, which blocks our rational brain from absorbing facts on the ground. When he keeps repeating that October 7 was the worst attack on Jewish people since the Holocaust, the idea is to stir feelings of persecution and unity. But the attack was not on “Jewish people.” It was an attack on a country — one that has been keeping Palestinians oppressed.

That fact is obvious to anyone who looks closely at Palestinian life in the West Bank. In the aftermath of October 7, one of my cousins said she had checked into my claims and determined that neither “occupation” nor “apartheid” applied there. I was disappointed but not really surprised: disinformation is hard to get past when you don’t have facts to challenge it. But Nelson Mandela, who recognized apartheid when he saw it, was haunted by the oppression of Palestinians until his death. Human rights groups like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Israel’s B’Tselem agree with his assessment, as do some former military generals in Israel. “Anyone who observes the reality on the ground can have no doubt about the nature of this regime, whereby three million Palestinians live under one set of laws and half a million Jewish settlers live under another set of laws,” said Omer Bartov, an Israeli professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown University, to Vox.

For doubters like my cousin, here is what Bartov means. While Jewish settlers are subject to civilian law, with its safeguards and rights to free speech, Palestinians live under much stricter military law, which defines a protest as illegal assembly. Children as young as twelve are tried in military court, where they are often interrogated blindfolded without a lawyer present and coerced to sign confessions in Hebrew, according to reports by Save the Children, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, and Military Court Watch. Conviction rates are nearly one hundred percent. But even without a conviction or charges, they can be detained indefinitely.

In everyday life, Palestinians are constantly harassed and treated as if they all were potential threats. The idea is to “create the feeling of being persecuted” to counter any temptation to cause trouble, said former IDF soldier Yehuda Shaul on France24. He described the nightly patrol for a typical pair of soldiers: “You walk in the streets of the old city of Hebron, break into a house. Not a house we have intelligence about — I’m the sergeant, I lead the patrol and choose a random house. Wake up the family, men on one side women on the other side, search the place… Climb to the roof, jump from one roof to another, come out through another house, wake the family. And basically that’s how you pass your eight-hour shift. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, from September 2000, when the second intifada started, until today.”

Shaul grew up in an Orthodox family and started his army service with a sense of purpose. He left as an activist for Palestinian rights who co-founded Breaking the Silence, a forum where disaffected IDF soldiers share testimony about the occupation. “What I did at the end of the day was enforcing our military rule over all the Palestinian people,” he said, “making sure they are stripped from dignity and freedom, that they don’t live as equals to us.” Aside from the endless checkpoints, where they can be strip searched or detained for hours, Palestinians can’t even drive on the same roads as Israelis or have the same access to water. If this isn’t apartheid, I’d like to know what my cousin would call it.

Incredibly, the average Israeli or diaspora Jew knows next to nothing about any of this, or about the gun-toting settlers who have been staging pogroms on Palestinian villages while the IDF watches. With few exceptions, Israeli news organizations avoid reporting about conditions within the territories, whether out of their own biases, fear of retribution, or their own ignorance. Foreign journalists, for their part, face challenges in the West Bank and are barred entirely from the Gaza Strip; only a handful have had permission to enter during the war, and only if embedded with the IDF.

In May, Israel expanded the news blackout by using a new “security” law to close Al Jazeera’s offices in Israel, block its website domestically, and ban local channels from airing its content. This is a big deal: not only is it the behavior of a dictatorship, but Al Jazeera is the lone international news organization with correspondents inside Gaza. Most media outlets have used its reports in some capacity during this war.

Palestinian journalists have paid a steep price for the being the world’s eyes and ears. More than a hundred have been killed, far more journalists than during any war in memory. In some cases, there is proof that the IDF targeted them; in others, there is strong suspicion. What is very clear is that Israel wants to control the narrative. Al Jazeera reporter Anas Al Sharif has said he has to change SIM cards five times a day, because Israel keeps blocking his phone signal. He has also received several messages from the IDF ordering him to leave the north, as he explained on an Al Jazeera report about the hardships journalists face in Gaza. When he stayed and kept reporting, his father was killed by an airstrike on their home. Another reporter in northern Gaza, Hossam Shabat, actually filmed himself and colleagues running from IDF bullets — while wearing clearly marked Press vests. Like Al Sharif, his home was bombed following a phone message to leave. “We built this house with our blood and sweat,” he wrote on X. “And now, my family of thirteen finds themselves living in a tent.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists has been scathing about Israel’s treatment of journalists, which started years before the Hamas attack. “We produced a report back in May of last year that identified a pattern of killings of mainly Palestinian journalists by the Israeli army with no accountability,” said the group’s CEO, Jodie Ginsberg. “So this pattern, and particularly one in which journalists are smeared as terrorists, is something we have frequently seen from Israel.”

Even filmmakers are subjected to institutional intimidation and threats. Israeli Yuval Abraham and Palestinian Basel Adra are co-writers and directors of No Other Land, a 2024 documentary about settler appropriation of the West Bank region where Adra lives. Their film won the best documentary award at the Berlin International Film Festival in February. I cried listening to Abraham’s speech:

“We are standing in front of you now, me and Basel are the same age… And in two days we will go back to a land where we are not equal… We live thirty minutes from one another, but I have voting rights. Basel is not having voting rights. I’m free to move where I want in this land. Basel is, like millions of Palestinians, locked in the occupied West Bank. This situation of apartheid between us, this inequality, it has to end.”

The next day, Israel’s ambassador to Germany vehemently attacked Abraham’s speech and the German cultural establishment on X. “Under the guise of freedom of expression and art, anti-Semitic and anti-Israel rhetoric is celebrated,” he wrote. “…Cultural so-called leaders, your silence is deafening.” Berlin’s mayor and other German politicians rushed to pile on condemnation of the speech. Abraham had to cancel his flight home due to death threats; his family in Israel went into hiding to escape a right-wing mob. I don’t know how Abraham controlled his rage over the absurd situation: an Israeli Jew, whose family members were murdered by Germans, was schooled and scolded by Germans about anti-Semitism.

This is not an isolated incident. Last fall, four US colleges tried to censor Israelism, a documentary film made by Jews about their Jewish experience — in the name of protecting Jewish students. The colleges had been bombarded by up to fifty thousand copy-paste emails generated by pro-Israel groups. “One email literally says that our film supports people who chant ‘kill the Jews,’ which is obviously very offensive and upsetting to us, as an almost entirely Jewish team of filmmakers,” co-director Sam Eilertsen told MovieWeb. What the film actually did was tell the story of Jews like myself, who discovered the truth about their history.

If I’ve given too many examples, it is because so many in my family and circle of friends are artists, writers, and actors who strongly oppose government censorship at the same time as they strongly believe that Israel is “the only democracy in the Middle East” — and don’t see a contradiction. But democracies have thick skin and don’t try to quash those that expose their secrets. Some Israeli officials even tried to strong-arm Netflix to deplatform Farha, a touching film about a Palestinian girl during the Nakba, because they insisted it was libelous propaganda.

The Farha commotion may sum up my anguish better than anything. Israelis know the pain of having their trauma denied; they even have a law against Holocaust denial. Why, then, do they stubbornly deny the Nakba and deprive Palestinians recognition of their own trauma? In a recent CNBC interview, Netanyahu gave me the answer. A Palestinian state would be “a tremendous reward,” he said — “a historic precedent of giving those people who committed the worst massacre against the Jewish people since the Holocaust on a single day, giving them a prize.”

There it is. Acknowledging the Nakba would mean acknowledging that Jews were rewarded with their own state after massacring and displacing Palestinians. It would explode this sanctimonious argument and place the Palestinian struggle for independence in proper context.

And so, they choose to lie instead.

“Were there no Israel, there wouldn’t be a Jew in the world that is safe,” Biden said at the White House Hanukkah party in December. I couldn’t disagree more, and couldn’t be more fed up with the Christians who keep speaking for me. My parents were born in the U.S. long before Israel existed. At what point did Israel take charge of my security? I resent that Biden has tossed my fate to the country that made me feel less safe in the first place, by linking all Jews to its atrocities.

I also feel less safe since the Israeli government stripped “anti-Semitism” of meaning and bite through overuse — while far-right, neo-fascist movements have been rising around the world. But Netanyahu doesn’t seem too concerned about them: he is busy forging alliances with their leaders, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Giorgia Meloni in Italy, Marine Le Pen in France, and Donald Trump. Orbán likes to peddle tropes about Jewish power cabals, yet is “a true friend of Israel” in Netanyahu’s opinion. Meloni presides over a party with fascist roots and sympathies. Our focus should be on these threats, not on students opposed to war.

I am proud of my Jewish heritage. I am proud of our commitment to scholarship, the arts, and activism, of our role in the civil rights and union movements. I am proud of the young Jews speaking out on college campuses and the older ones who took over the Cannon Building in the Capitol last November. This is the culture that I know and connect with — people whose hearts are capable of aching for the Israeli hostages and the Palestinians at the same time.

There is a corresponding movement of peace activists in Israel who work on everything from water rights to the treatment of Palestinian children in detention, and even offer themselves as human shields to keep settlers from attacking aid trucks or West Bank olive harvests. But with the exception of this very brave minority, I don’t feel a cultural connection to Israelis who I meet or see in the news. What I see is an openly racist society where a rap song calling for the death of Dua Lipa and Bella Hadid (among many others) can top the charts. Where a news anchor can refer to Palestinians as “these animals” to audience applause, and a colleague on another channel can demand “a lot more rivers of Gazans’ blood” without risking his job. Where a large majority of the population can oppose humanitarian aid to Gaza and more than half can think that the destruction there has been insufficient.

Those who accuse Israel of oppression are quickly admonished with “shame on you” — how dare you call victims the perpetrators? That was the crux of Israel’s defense to South Africa’s eighty-four page accusation of genocide before the International Court of Justice. According to Brown professor Bartov, who has written several books on the Holocaust, it is not unusual for countries to progress from oppressed to oppressor without realizing. “Groups that engage in a great deal of violence against other groups often do that because they see themselves as victims,” he said on Owen Jones’s YouTube channel. “And they see themselves very often as victims of those that they are killing. This kind of cycle of victims becoming perpetrators, you actually take it back to the Germans, who saw themselves as the great victim of World War I, of the unjust peace, of the stab in the back by the Socialists and the Jews.”

Netanyahu and others keep invoking Germany of the Thirties to describe the current situation and atmosphere. Some of us see Germany, too — just not the way he does. Writer Masha Gessen, whose grandmother’s family was largely wiped out during the Holocaust, wrote a New Yorker essay that compared Gaza to a Jewish ghetto and Israel’s current campaign to liquidation by the Nazis. That essay caused an uproar, but Israelis have themselves voiced similar opinions.

A prominent Israeli philosopher, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, coined the term “Judeo-Nazis” decades ago to describe soldiers in the occupied Palestinian territories. And months before the current war began, a former IDF general compared “apartheid” (his word) in the West Bank to what Jews experienced under the Nazis. “Walk around Hebron, look at the streets,” said Amiram Levin, who had been chief of Israel’s Northern Command, to Haaretz. “Streets where Arabs are no longer allowed to go on, only Jews. That’s exactly what happened there, in that dark country.” Like Leibowitz before him, he believes that the occupation has left the military morally bankrupt, “rotting from the inside.”

It is frankly terrifying to make such comparisons in public: the backlash is swift and fierce, and if Republicans in Congress get their way, may include arrest. But the parallels are inescapable. Many times during this war I have had the chilling sensation of watching an old newsreel. The blindfolded, half-naked Palestinian detainees kneeling in front of a ditch, which some later said they thought would be their grave, was one. Another was seeing detainees numbered. And it is hard not to think of concentration camps when confronted with the emaciated bodies of children in northern Gaza, or men returning from detention. According to Alex de Waal, an expert on famine and director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University, the first thing Germany tried as part of the Final Solution was the Hunger Plan, which used starvation as a weapon of war. They switched tactics when it didn’t work fast enough, de Waal said in an online interview, but in the end starvation took the most lives.

I have been letting all this marinate for seven months, as I researched and wrote. Immersed in the suffering of Palestinians, I needed to understand how so many in my community could trivialize or even laugh at it. What kept floating to the top was the damage that I think comes from elevating the Holocaust above all other atrocities and making comparisons a sin or crime. For starters, defining Jewish trauma as more important has left Israelis and many diaspora Jews blind to the pain of others, especially if it overlaps their own. I have been shocked by the black and white thinking, as if caring for Palestinian lives means you supported the October 7 attack.

Forbidding comparison to the Holocaust invites history to repeat itself. “I think that we have a moral and one could also argue, legal obligation to compare the Holocaust and the atrocities committed during the Second World War to the present,” Gessen said on NPR. “If we take the promise of never again seriously, we once again have to constantly be asking ourselves, ‘are we laying the foundations for the mass murder of millions of people? Are we employing or is part of the world employing the same kinds of tactics that were employed by the Nazis?’ I think there’s every reason to say that that is exactly what’s happening.”

There are parallels as well in the West Bank, where violent, unchecked nationalism from the half million Israeli settlers “threatens not only Palestinians living in the occupied territories but also the State of Israel itself,” according to a New York Times investigation in May. Some in Israel have been warning about this threat, too, for decades. In 1995, in the aftermath of a mass murder of Palestinians by an extremist settler, historian Moshe Zimmermann was quoted as saying that the children of settlers were being indoctrinated with hatred and pumped with delusions of superiority, which reminded him of German youth.

His words ran through my head yesterday, while watching a young border guard near Bethlehem who had been secretly recorded by a bus passenger. Boarding the bus filled with Palestinians, he insulted and berated them before weirdly singing Israeli nationalist songs with the bus driver’s microphone. There was something in his smug superiority that already haunts me.

I’m beginning to understand that the world has allowed a genocide to continue for seven months because a lot of people can’t accept that Jews can be inhumane. Despite the documented targeting of aid workers, doctors, and journalists; despite acts of breathtaking cruelty shared by perpetrators on social media; despite an engineered famine, the notion that Jews can be barbaric and Muslims can be tyrannized still feels counterintuitive and impossible to many in the Global North, especially to older generations. In the Jewish community, there is a deep sense that we aren’t capable of such evil.

It is time to recognize that Jews aren’t exceptional or exempt, and that allowing a country to act with impunity for years does tremendous harm to its national psyche. “The most disturbing lesson I learned while covering armed conflicts for two decades is that we all have the capacity, with little prodding, to become willing executioners,” said Chris Hedges, who covered the Bosnian, Gulf, and Iraq wars for the New York Times. “The line between the victim and the victimizer is razor thin. The dark lusts of racial and ethnic supremacy, of vengeance and hate, of the eradication of those we condemn as embodying evil are poisons that are not circumscribed by race, nationality, ethnicity or religion. We can all become Nazis.”

I have been scared to put my thoughts in print, knowing what will come back at me. I am even more scared about the state of my relationship with friends and family. Months ago, my much-loved cousin asked “can’t we agree to disagree?” In any other circumstance my answer would be unequivocally yes. But the voice of my parents would echo in my head if I agreed to overlook this subject. Over the years, they returned to a question that gnawed at them: how did ordinary Germans carry on with their lives and stay silent? My parents never forgave the silent ones, never would set foot in Germany, never would buy a German car.

I can’t agree to disagree.

As Haaretz’s Levy said: “One day Israelis will be asked, ‘where have you been? You knew all this, what did you do about it?’”